Why Did Single Women Only Wear White Dresses to Balls

The period known in American history as "The Gilded Age" spanned the last three decades of the nineteenth century (roughly 1870-1900). Here in Hyde Park, New York, the National Park Service preserves Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, one of the many Gilded Age mansions owned by Frederick and Louise Vanderbilt. Our mission at the Vanderbilt Mansion is to interpret Gilded Age culture. And fashion was a significant part of that culture.

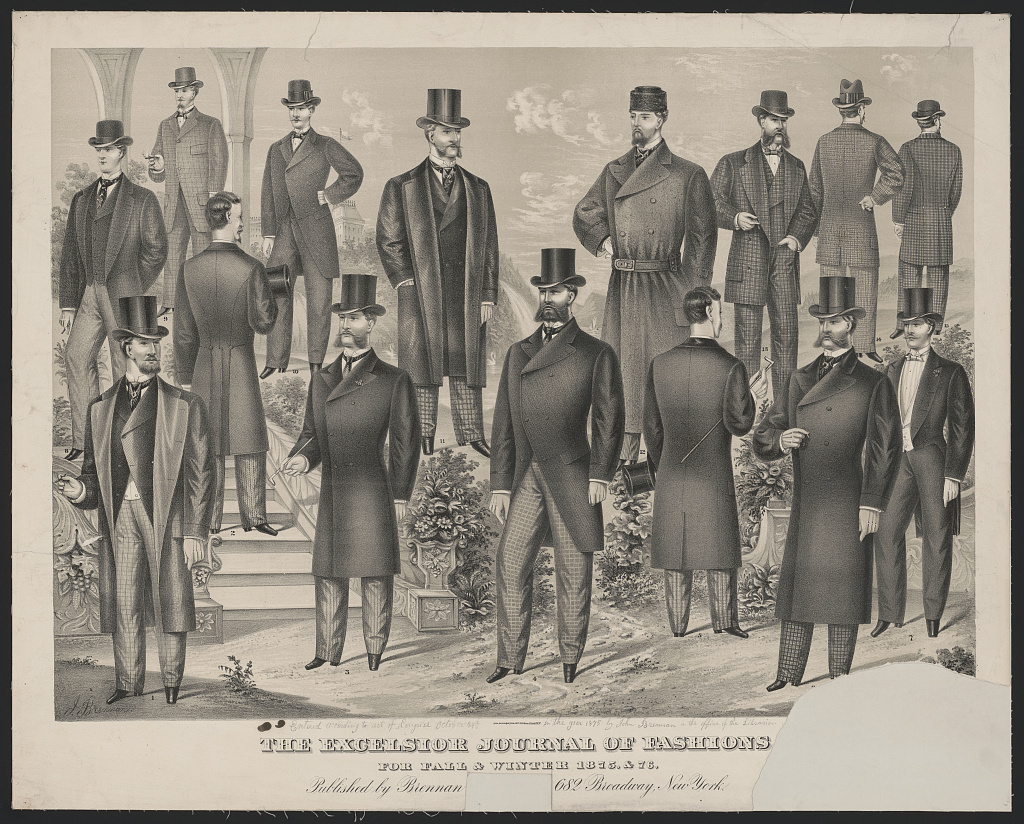

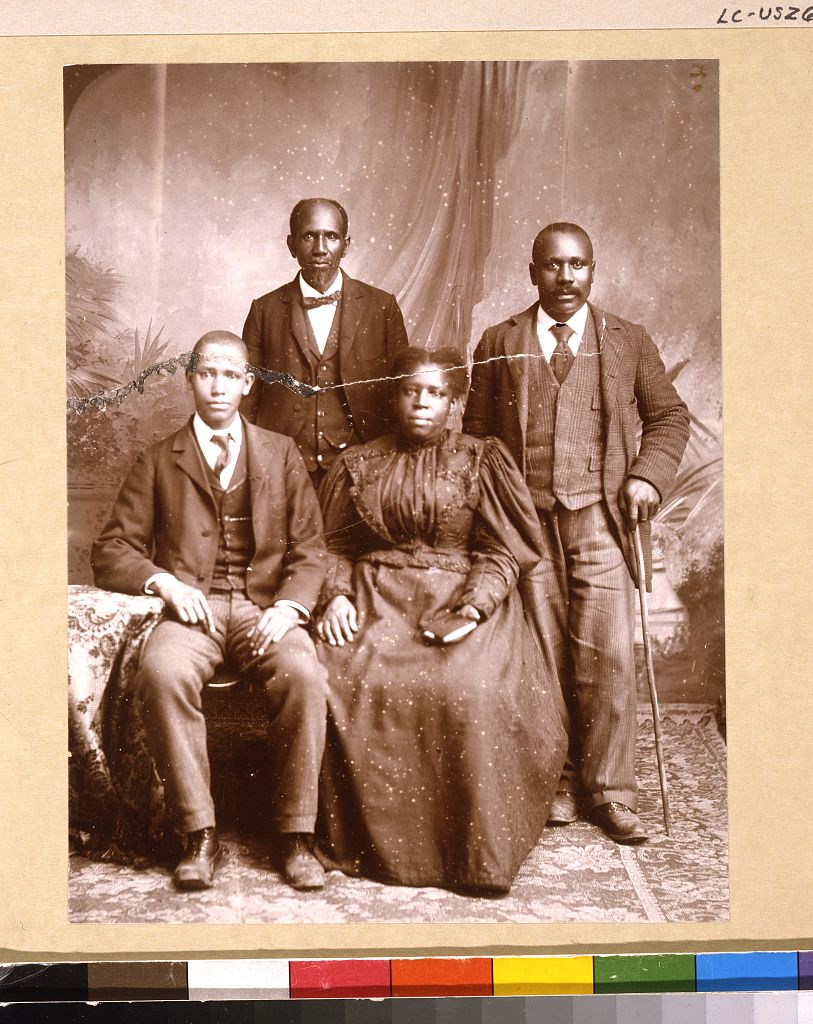

Generally, during the Gilded Age, men and women wore many layers of clothing. Men's styles were predominately different variations of suits and women's styles were floor-length dresses. Ensembles in this era were very formal by today's standards. Women wore restrictive corsets to achieve desired silhouettes. Furthermore, both men and women were expected to change clothing as many times per day as their social status and wealth would allow. It was common for the wealthy to have different clothing for the morning, afternoon, and evening. Just as in any period in history, fashion during the Gilded Age was dynamic. The styles that were chic in 1870 became passé by the turn of the twentieth century. Here is an overview of how fashion changed by decade during the Gilded Age:

1870s

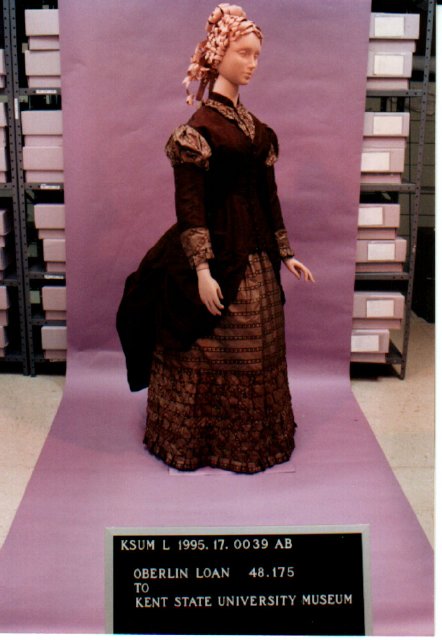

One of the most iconic elements of women's fashion in the 1870s and 1880s was the bustle. This meant they were fuller in the back than in the front, rather than being circular. Clothing was often vibrantly colored, thanks to the increased use of synthetic dyes, which were still a fairly new innovation. Furthermore, women's clothing featured multiple colors in the same outfit, something that was uncommon prior to this decade. It was fashionable to layer vibrant colors on top of dark ones. A popular combination was plum and navy blue.[1] Around 1876, the "princess line" style became popular. This encompassed bodices and corsets with vertical seams, rather than horizontal ones which tightly hugged the body of the wearer. Long sleeves and high necklines were also features of this style, which was named for the Alexandra, the Princess of Wales. On this style, Harper's Bazar wrote:

"The object now is to make the figure look slender and long-waisted…There are many dresses with the long seams that begin on the shoulders, making long side bodices, while others again have the short seams that begin in the armhole…The neck of the dress is as high as it is possible to wear it, and in many cases has two collars, one of which stands, while the other is turned down in Byron shape…Sometimes there is a single plastron[2] down the middle, while others have two plastrons set on a little beyond the button holes. This a tasteful and simple fashion."[3]

To top off ensembles, such as those in the princess line style, it was common for women to wear very intricate hairstyles. Menswear of the 1870s featured multi-piece suits, the most popular among which were the morning coat and frock coat as everyday styles. A top hat could be worn with either. Among the working class, the sack coat became a favorite, which was often worn with a bowler hat. Facial hair was also all the rage.

This print shows women wearing dresses with bustles(Library of Congress)

This print shows women wearing dresses with bustles(Library of Congress)

Print showing multiple colors in the same outfit, 1876 (Library of Congress)

Print showing multiple colors in the same outfit, 1876 (Library of Congress)

A dress in the princess line style(Kent State University)

(Kent State University)

Almost all of the women in this group photo are wearing dresses in the princess line style, 1880s (Library of Congress)

Almost all of the women in this group photo are wearing dresses in the princess line style, 1880s (Library of Congress)

Men's fashions, winter 1875-1876 (Library of Congress)

1880s

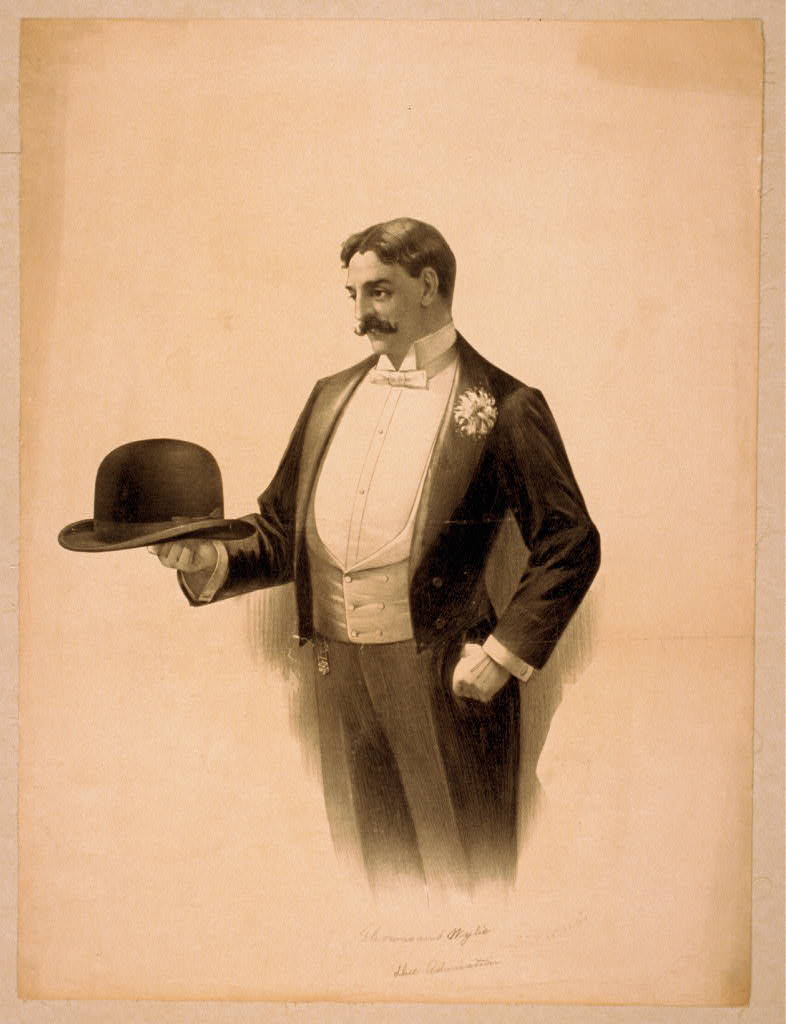

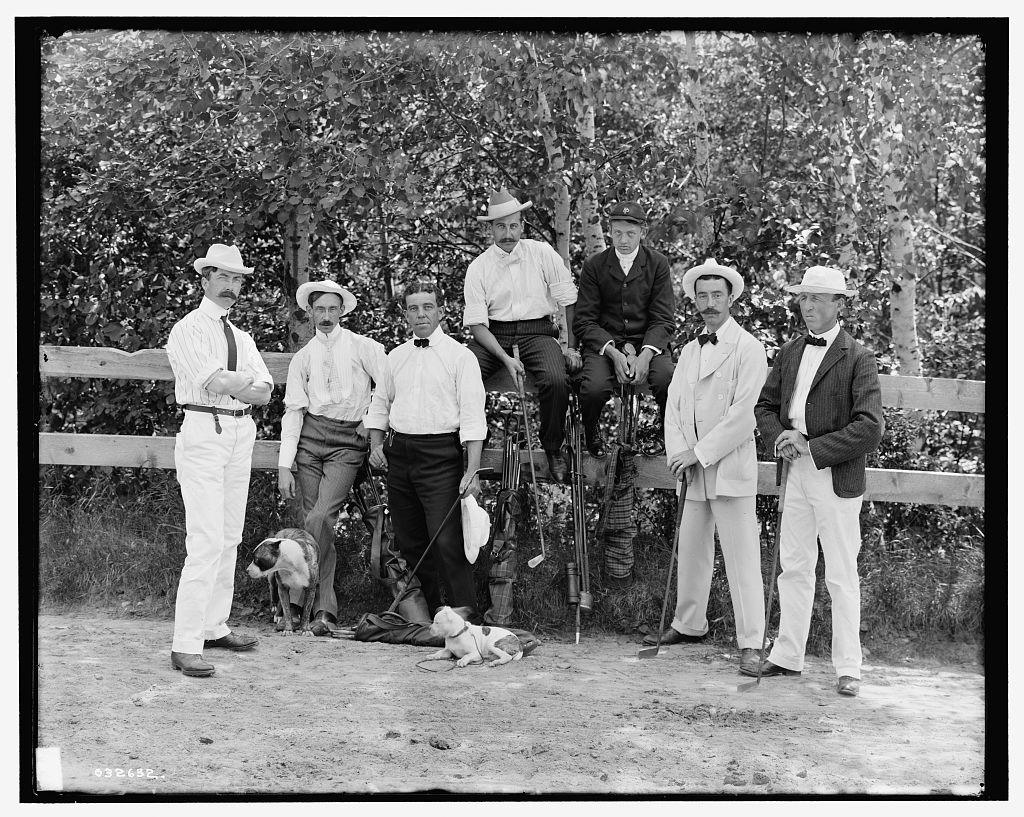

Women's fashion of the 1880s saw a continuation of the "princess line" style and bustles, though in this decade bustles became more elaborate and often required complex undergarments to support their growing size. These included cushions stuffed with hair and attached to a belt, or even steel springs to achieve the desired look. Day and evening wear were steeped in decoration: bows, lace, frills, and more. For example, an 1888 issue of Harper's Bazar described a dress with "…metallic embroideries of silk cords, and beads-gold, silver, steel, jet and crystal…so incrusted with metallic embroidery as to conceal the fabric on which it is wrought."[4] Skirts were commonly bunched in some way to reveal a woman's underskirt. Hairstyles were simpler than in the 1870s. This is due to the popularity of highly embellished hats that included everything from lace and flowers to feathers and whole birds. Menswear in this decade became less baggy. Popular informal options included the sack suit and double or single-breasted suits without waist seams. One of the most notable additions to menswear in this decade was the tuxedo. Though reportedly first produced for the UK's Prince Albert in 1865, the tuxedo saw a huge boost in popularity in America at the end of the 1880s. A man named James Potter is said to have brought the style from England to America, where he wore it to a country club ball in Tuxedo Park, New York (hence, the name tuxedo to describe the ensemble). In addition to the tuxedo as a new option in formalwear, clothing to be worn expressly for sporting activities, or sportswear, became highly popular among men.

A dress with a skirt bunched to reveal a patterned underskirt, a popular style in the 1880s (Kent State University)

The well-known tuxedo first gained popularity in America in the 1880s (Library of Congress)

The well-known tuxedo first gained popularity in America in the 1880s (Library of Congress)

These ensembles were considered sportswear for men in the 1880s and 1890s (Library of Congress)

These ensembles were considered sportswear for men in the 1880s and 1890s (Library of Congress)

1890s

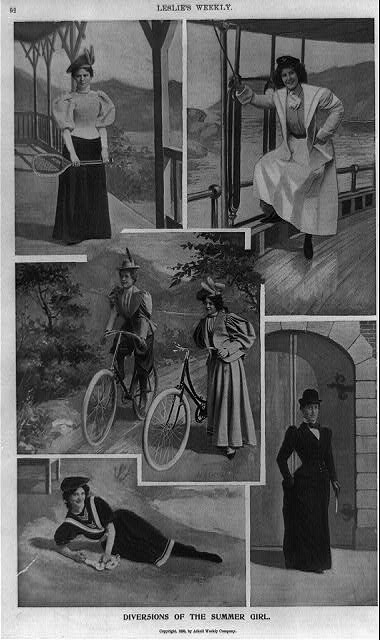

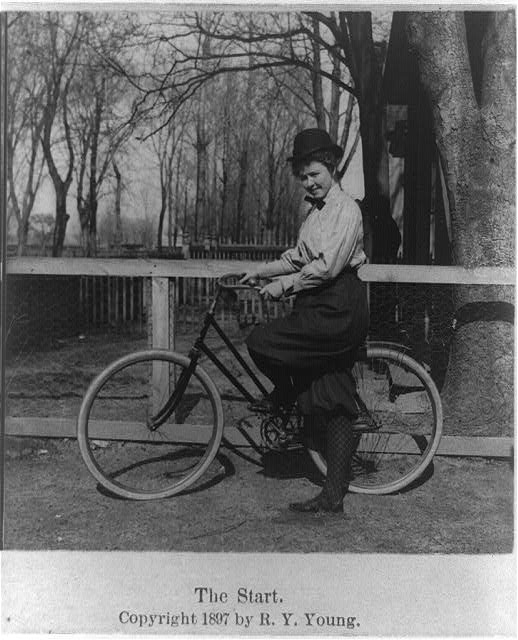

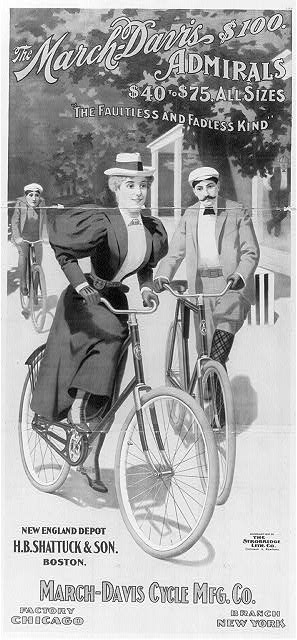

In the last decade of the Gilded Age, fashion for men and women looked toward the upcoming twentieth century. Women began to spend more time outside the home, both at work and at play. In turn, fashion responded. Sportswear for women became highly popular, just as it had for men in the 1880s. While a far cry from the athleticwear of today, in terms of simplicity and movability, women now had clothing options more suitable for activities newly socially acceptable to them, like cycling, golf, and tennis. One notable sportswear option was the "bicycling costume," which was basically a cross between a skirt and pants. In a time before pants for women were acceptable, bicycling costumes were somewhat controversial. Most women, instead, wore slightly shorter skirts or skirts with a deep pleat in the back while cycling. The shirtwaist ensemble also became a popular option for both sportswear and office work. This consisted of a long skirt with a shirt that was tailored like a men's dress shirt, but was feminized with bright colors, lace, frills, and other trimmings. Gone were the distinctive bustles of the previous two decades, which were replaced by bell-shaped skirts. Additionally, puffy sleeves became all the rage. The 1890s also saw variations in sleeve length and necklines, depending on the time of day an ensemble was to be worn. Morningwear featured high collars and long sleeves. Afternoon ensembles opened at the neck and usually featured short sleeves. Furthermore, evening gowns of this decade commonly exposed their wearers' chests and shoulders. Prominent in this decade in menswear were stiff, high collars. Jackets were more frequently left unbuttoned, and it was common for shirts and waistcoats to be brightly colored. It was very fashionable for men to carry ornate canes made from cherry or oak as they strolled around town. Sportswear for men continued to be popular in the 1890s, just as it had been in the previous decade. The frock coat remained a popular daywear option.

This print shows various sportswear options for women of the 1890s (Library of Congress)

This woman is sporting the infamous bicycle costume (Library of Congress)

This print depicts a more socially acceptable outfit for woman cyclist (Library of Congress)

Each in this group of ladies are sporting shirtwaist ensembles (Library of Congress)

Each in this group of ladies are sporting shirtwaist ensembles (Library of Congress)

This gown is a great example of how fashions changed in the 1890s. Note the puffy sleeves and the absence of a bustle. (Kent State University)

(Kent State University)

The men in this photo are wearing styles that were popular in the 1890s (Library of Congress)

The men in this photo are wearing styles that were popular in the 1890s (Library of Congress)

Charles Worth

Known as "the father of haute couture", Charles Frederick Worth was one of the premier fashion designers of the Gilded Age. Worth got his start in his native England as an apprentice for dressmakers and cloth merchants in London. As a young man he moved to France, where he found employment as a salesman for the firm Gagelin-Opigez & Cie, which sold high-end textiles and ready-made clothing. He started his own business in 1858, which later became known as The House of Worth. The Worth name went on to become synonymous with wealth and exclusivity. But the House of Worth was not only exclusive, it was also innovative. Clients would visit the House's lavish Paris salon, rather than having Worth dressmakers come to their homes, as had been customary. Worth was also the first to "sign" his dresses, by putting his name on dress labels. Furthermore, he was a pioneer in promoting his brand using print media. Worth designs were notable for detailed trimmings and decorative ornaments, as well as their acknowledgement of historical fashion trends. These elements caught the eye of Empress Eugenie, wife of French Emperor Napoleon III, and she became one of Worth's most important patrons. Her support of Worth was a huge factor in the success of his fashion house. The House was known to make one-of-a-kind pieces for wealthy clients like Empress Eugenie as well as many women from America's upper crust, like the Vanderbilt's. The dress that Alice Vanderbilt wore to her sister-in-law Alva's famous fancy dress ball in 1883 was designed by the House of Worth. The Gilded Age was the height of popularity for the House of Worth. After Charles Worth's death in 1895, his sons Gaston-Lucien and Jean-Phillippe carried on the illustrious fashion house, though with changing styles and the advent of the ready-to-wear clothing industry, the House of Worth failed to hold the same prestige it did during its heyday. The business closed its doors in 1952, when Charles Worth's great-grandson, Jean-Charles, retired. The House of Worth was a powerhouse in the world of Gilded Age fashion that produced some of the most lavish styles in a period known for its opulence. Charles Worth, the "father of haute couture", was one of the first assert high fashion as an artform, thereby revolutionizing the fashion industry in ways still felt today.

An 1880s Worth ball gown (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

An 1880s Worth ball gown (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Alice Vanderbilt (Frederick's sister-in-law) as an electric light, 1883. This gown was deigned by the House of Worth (New York Historical Society)

Worth wedding dress, 1890s (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Worth wedding dress, 1890s (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The Aesthetic Dress Movement of the 1870s and 1880s

Embraced by artists and reformers, the Aesthetic Dress Movement of the 1870s and 1880s was a non-mainstream movement within fashion that looked to the Renaissance and Rococo periods for inspiration. The movement began in response to reformers seeking to call attention to the unhealthy side effects of wearing a corset, thus, the main feature of this movement in women's dress was the loose-fitting dress, which was worn without a corset. Artists and progressive social reformers embraced the Aesthetic Dress movement by appearing uncorseted and in loose-fitting dresses in public. For many that fell into these categories, Aesthetic Dress was an artistic statement. Appearing in public uncorseted was considered controversial for women, as it suggested intimacy. In fact, many women across the country were arrested for appearing in public wearing Aesthetic costumes, as authorities and more conservative citizens associated this type of dress with prostitution.

But for most wealthy women, the influence of the Aesthetic Dress movement on their wardrobes took the form of the Tea Gowns. Like most dresses that could be considered "Aesthetic," Tea Gowns were loose and meant to be worn without a corset. However, they were less controversial than the Aesthetic ensembles of more artistic and progressive women. This is because they were not typically worn in public or in the company of the opposite sex. Tea Gowns were a common ensemble for hosts of all-female teas that were held in the wearer's home. Thus, because no men were in attendance, Tea Gowns were socially acceptable in these scenarios. Mainstream magazines like Harper's Bazar were not especially keen on the Tea Gown and cautioned their readers not to appear wearing one in public. The January 26, 1884 issue proclaimed: "…it is not convenable, according to European ideas, to wear a loose flowing robe of the tea-gown pattern out of one's bedroom or boudoir. It has been done by ignorant people at a watering-place, but it never looks well. It is really an undress, although lace and satin may be used in its composition. A plain, high, and tight-fitting garment is much the more elegant dress for the afternoon teas as we give them."[5]

A tea gown (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

A tea gown (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

(Metropolitan Musuem of Art)

(Metropolitan Musuem of Art)

Another example of a tea gown. Note the Renaissance influence. (Metropolitan Musuem of Art)

Another example of a tea gown. Note the Renaissance influence. (Metropolitan Musuem of Art)

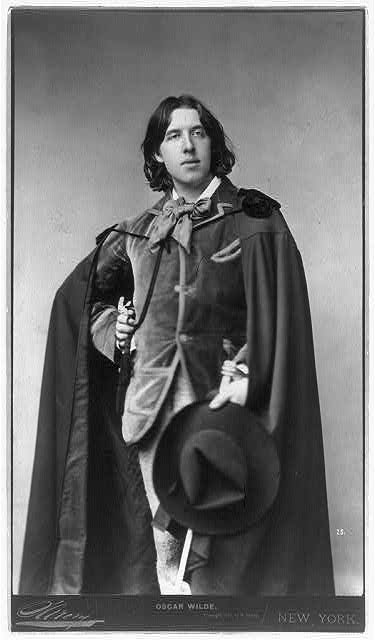

Like the Aesthetic gowns worn in public, Tea Gowns borrowed from Classical forms. In doing so, these dresses were meant to suggest that their wearer had artistic knowledge. The Aesthetic Dress movement also had an impact on men's fashion. Just as with women, artistic men embraced this style of dress, wearing "theatrical" clothing, bright colors, and tight pants. For men, Aesthetic Dress was even more out of the mainstream, as it was commonly associated with homosexuality. The biggest proponent of male Aesthetic dress was writer Oscar Wilde, who gave lectures across the country on its benefits. The Aesthetic Dress movement faded in the 1890s in response to multiple factors. These included a return to traditional ideas of "manliness" that made male Aesthetic costumes unacceptable. Furthermore, non-corseted styles for women became more mainstream in the 1890s, thanks to the work of dress reform groups and the advent of ready-to-wear garments.

Oscar Wilde in an Aesthetic costume (Library of Congress)

Influenced by trend, technology, artists, and reformers, fashion in the Gilded Age was grand and showy for the wealthy, like the Vanderbilt's, but much less so for those with lower incomes. The styles of this period seem incredibly formal compared with the athleisure and jeans that make up today's everyday attire. They certainly contribute to the awe and fascination many feel towards the Gilded Age culture that we interpret and preserve here at Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site.

Bibliography

[2] A plastron is a section of trim on the front of a bodice

[3]Harper's Bazar, Volume IX, No. 40, 627

[4]Harper's Bazar, Volume XXI, No. 10, 151

[5] "Afternoon Tea," Harper's Bazar vol. 17, no. 4 (January 26, 1884), 50-51

Source: https://www.nps.gov/elro/blogs/gilded-age-fashion.htm